REHABILITATION OF FLYING-FOXES

The purpose of wildlife care is to release animals back into the wild. If an animal is unable to survive in the wild due to its injuries or disability, it is un-fit for release.

Rules And Regulations

Caring for injured wildlife requires a rehabilitation permit. In Queensland this is issued by the Department of Environment and Science (DES) of the Queensland Government.

And as flying foxes and microbats are a protected species, there is also a strict Code of Practice for the Care of Sick, Injured or Orphaned Protected Animals in Queensland, Nature Conservation Act 1992.

The End Game

The rehabilitation of bats is dependent on the type and extent of the injury or illness. The aim of wildlife care and rescue is to get that animal back into the wild with all the abilities it needs to fend for itself.

Most important is that it will also live a normal productive and pain free life.

And whilst many injuries may initially look terrible, with dedicated experienced care there are many stories of quite amazing results.

TYPES OF INJURIES

The nature of the injury determines the length and course of a bat’s rehabilitation.

Entanglement injuries (most commonly netting, fishing line and barbed wire) usually affect the wings of bats, although feet and legs can also be badly injured.

The wing membrane has incredible healing capacity and even a fairly large hole will heal well in a relatively short timeframe. However, there are times when the membrane is simply too damaged and the tissue ‘dies back’ right to the edge of the wing. And without sufficient surface area, the bat is unable to fly.

Fractures can sometimes be splinted or pinned.

Infections such as pneumonia, internal parasites, ‘wet wing’, Candida or wound infections for example, can all be treated.

A Place For Euthanasia

But for some bats, their future may not be that ‘rosy’. Bats suspected to be infected with Lyssavirus or Rat Lungworm are euthanised as the disease progresses to a slow and painful death.

Some injuries are also just too severe to treat or survive. Fractures to the spine or wing bones, especially if close to joints are deadly to a bat.

And severe arthritis of the flying joints can result in chronic pain affecting a bat’s ability to fly.

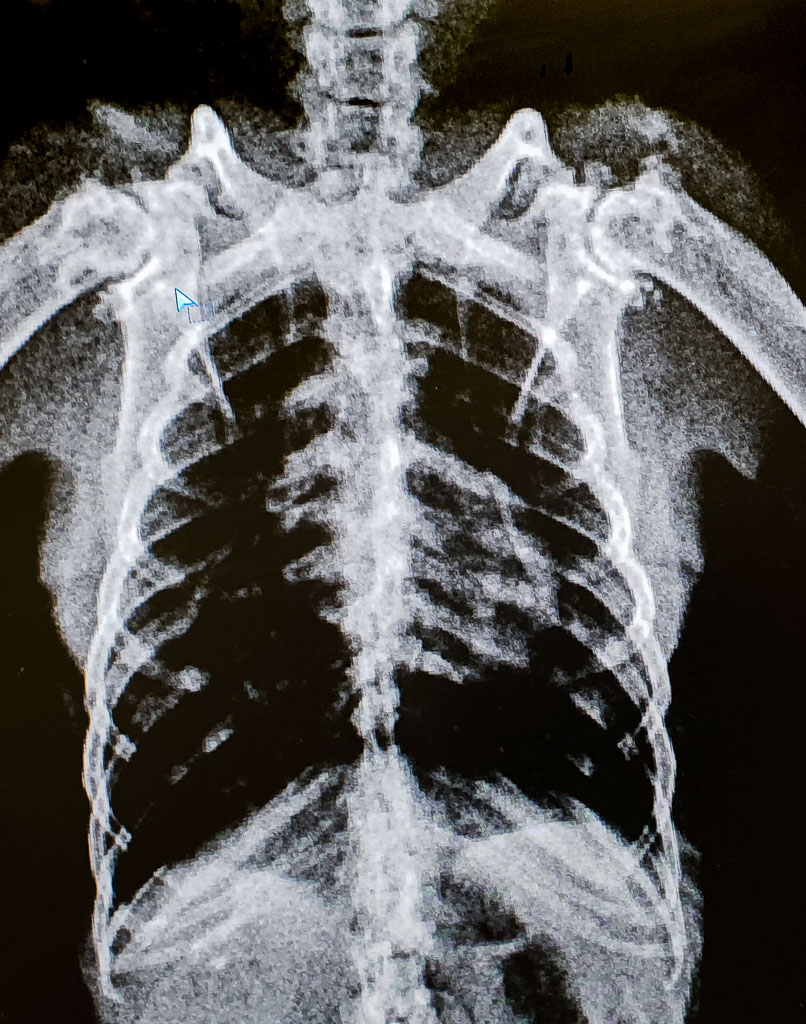

Severe painful arthritis in both shoulders of a rescued old Black Flying-fox.

The Queensland Government Code of Practice dictates in detail the objectives to be met during care and rehabilitation of protected wildlife such as bats.

There are distinct guidelines for euthanasia. These include circumstances where bats may be suffering or have a poor prognosis for survival.

As that dictates their inability to be released to the wild, they must be euthanised under this legislation.

Educational Ambassadors

However, there are exceptional circumstances under which an animal may be kept in permanent care.

Under special permission from the DES, a bat may be allowed to enter the Queensland Species Management Plan (QSMP). It can then become an Educational Ambassador for its kind.

Veterinary Assistance

An experienced bat Carer, some with over 30 years expertise caring for bats, often has a great deal of practical knowledge in the caring for bats including the diagnosis of illness or injuries.

Veterinary advice about flying-fox health and treatment can be difficult as there are few Vets with the experience or knowledge of how to treat these animals correctly.

Thankfully there are some dedicated Veterinarians who keep their own ABLV (anti-rabies) vaccinations up to date so they are able to give their time and energy to assist Carers rehabilitate sick and injured bats.

Veterinary Surgeons who donate their consultation time (often out of hours or round the clock) to attend wildlife patients are an invaluable support to volunteer wildlife Carers.

This often includes a radiology service as well as medication advice and supply. This very much appreciated service provides an exceptional role for the care and rehabilitation of our injured native wildlife.

As Bat Rescue Inc., we would like to give a special thanks to all our Vets who offer our organisation this highly valued Veterinary medical support.

STAGES OF REHAB TO RELEASE

Early Orphan Care

Rehabilitation of Flying-foxes can begin with premature baby bats to orphaned older babies. This is where we always need especially baby bat carers in the Flying-fox breeding season.

From about the age of 3-4 weeks to about 8-10 weeks, baby bats are given muscle strengthening exercises. This includes spending increasing amounts of time hanging.

Usually this involves the use of simple cheap laundry airers. These innovative home ‘batty gyms’ can have suspended ropes, tea-towel hammocks or hanging soft toys.

But once a baby flying-fox discovers its wings, it goes through a stage of learning to fly. This is when it becomes a ‘flappy bat’!

Once they become more adventurous and learn how to take off, you had better beware. Nothing in your house is sacred when a baby bat decides to launch itself and start to fly around your living room!

Pre-Creche

So this generally is the time to place your baby into a pre-creche facility. This is usually a small to medium sized aviary which allows for flight practice.

They must have soft floors so those early flight failures don’t result in un-necessary injuries.

Plus it is also time to introduce your baby to other baby bats. This starts the process of socialisation and learning how to become a bat (and not a baby human!).

Creche

Juvenile flying-foxes eventually progress to creche which is really just a larger flight aviary. But to do this they first have to qualify for a creche intake (just like human kids!).

They have to be at least 13 weeks old, fully weaned off milk formula feeds and able to eat chunky fruit un-aided.

This is also the point where human contact is withdrawn as much as possible. This is to eliminate any residual human imprinting and is essential for their future in the wild. They need to be re-taught not to recognise humans as friends and a source of food.

In fact, if at this stage a bat demonstrates fear of humans entering the aviary, then this is just the kind of bat you want to see.

Over the next 3-4 weeks they hopefully expand their flying skills. And they also need to learn to interact with other bats as if in a wild colony or flying-fox roost.

Every picture tells a wonderful story. So we hope you enjoy watching some of these cute videos!:

- Flying-foxes From Bat Rescue’s Creche of 2017

- More Flying-foxes From Bat Rescue’s Second Creche of 2017

- Flying-foxes from Bat Rescue’s Creche of 2016

Release And Final Freedom!

After at least 3 weeks in a large creche aviary, the bats are ‘flight tested’. This is to make sure they have developed the muscle tone and regained or developed the ability to use their flight muscles.

Once successful, they can be ‘soft-released’ from an aviary to a nearby colony of wild bats. The hatch from the aviary is regularly opened at dusk to allow them to fly out to hopefully re-join their wild cousins.

This can take about a week, with encouragement by gradually reducing the food within the aviary. Some food is also placed outside the aviary in case some bats are a little scared to go too far initially. However this too is reduced over the week.

This staged process encourages the bats to seek out their own food hopefully following in the footsteps (or flight path!) of their wild family.

It is always extremely gratifying to be able to release a bat that would otherwise have died had it not spent time in care.

So, one by one they fly off. Some may return for a short while until they gain confidence out in the wild. But then they are gone for good.

Success at last. And a job well done!